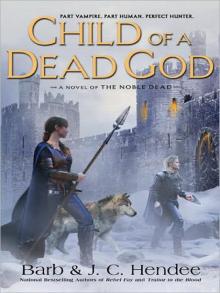

Child of a Dead God Read online

Page 2

Looking about the entry room, his gaze passed over the withered remains of the young priest.

How long had he lain here unconscious?

The hearth’s fire still burned as if recently fueled. A tin kettle rested near it, faint wisps of steam rising from its spout. And the cold breeze . . .

The front door was ajar.

Chane glanced up the dark stairwell. Not a sound came from above. All was silent but for the crackle of the flames and the cold air spilling around the open door. He struggled to his feet.

Twice risen, Welstiel had said, only in his first year of death. Less than a full season past, Chane had been beheaded, and Welstiel had somehow brought him back. The only evidence that it had ever happened was the scar line around Chane’s throat—and his forever maimed voice. Some among the dead would say he had been fortunate indeed.

Yet he had just tried to face an experienced undead freshly gorged on life.

Despite festering resentment, Chane acknowledged his own foolishness.

He tottered and bent over to brace his hands against his knees. His left shoulder and elbow burned as if filled with embedded needles. And now he was truly hungry. His dead flesh ached for life with which to repair itself.

But why was the front door open?

Chane stumbled over, pulling it wide. Falling snow swirled in the darkness outside, and he heard a grunt off to the left.

Welstiel knelt in a drift, still naked to the waist. Thin trails of steam rose from bloodstains on his arms and chest. He leaned down, scooping armfuls of snow, and splashed it over himself, scrubbing furiously. He repeated the process over and over.

“Why?” Chane asked.

Welstiel lifted his head. Flakes of snow clung to the locks down his forehead. When his gaze landed on Chane, his expression shifted from numb horror to startled wariness.

“Awake, are you?” he asked quietly, and rose to his feet. “And reason returns once more . . . for the moment . . . but always with one foot perched upon the Feral Path.”

“What are you babbling about?” Chane rasped, though that last strange reference seemed familiar.

He tensed as Welstiel approached, but he was in no condition for another fight.

“Perhaps I should not help you reach your sages,” Welstiel went on, but he stared into the gorge, as if alone. “Monster with a mind . . .”

Chane hesitated. Welstiel had promised him letters of introduction to gain acceptance at one of the sages’ main branches, across the sea—in exchange for Chane’s obedient service on this journey.

“A beast,” Welstiel whispered mockingly, “sent in among the learned of the cattle.”

That last word, which Chane had used so often, suggested Welstiel was fully aware of his presence, but the tone made Chane’s instincts sharpen in warning. He sidestepped toward the switchback path down the gorge’s sheer face, ready to bolt.

“Get back inside!” Welstiel ordered.

Chane halted.

Welstiel stood as still as ice, a pale column of flesh surrounded in a swirling white snowfall.

Chane longed for the denied pleasure of a feast. Sustaining draughts from Welstiel’s cup might fuel him more than feeding would, but they left him painfully unsatisfied in other ways. But the existence he most desired still awaited him, where he would spend his nights studying history and languages in a sages’ guild. He closed his eyes and saw Wynn’s oval face. Could he attain this world on his own and no longer suffer Welstiel’s madness?

“Now,” Welstiel demanded. “Or stay and burn in the sun!”

Chane raised his eyes to the sky.

In the east, a faint glow exposed the black silhouette of the gorge’s distant ridge. Where in this desolate place would he find shelter if he ran? He backed into the entry room as Welstiel followed, slamming the door shut.

“Sit,” Welstiel instructed. “I will have need of you soon . . . to guard them until they rise.”

Chane looked to the dark stairwell and finally understood.

Once before he had watched an undead feed to bursting and disgorge all it had swallowed. In faraway Bela he had crouched in an alley while his maker, Toret, took his time in choosing and killing two sailors, who rose the next nightfall as undead servants.

“You are making more of our kind?” Chane asked.

Welstiel crossed to the room’s front corner and crouched to dig through his pack.

Chane remembered something else of Toret’s efforts, and glanced at Welstiel’s bare forearms. He saw no slashes there by which Welstiel would have force-fed his own fluids to his creations.

“They will not rise,” Chane hissed. “You have not fed them from yourself.”

Welstiel clicked his tongue in disgust. “More superstition . . . even among our kind.”

Although this was not the first correction Chane had received in his new existence, he knew better than to question it. But if feeding the victim one’s own fluid was not necessary, then why did one victim rise from death while another did not?

Chane’s thoughts turned to the small cells lining the upper passage. He tried to count off the number of those locked away.

“How many?” he asked.

“We will not know until tomorrow’s nightfall,” Welstiel answered, making certain the front window shutters were soundly latched against the sun. “I took ten.”

Chane stared at him. Toret had taken only two at once, and the act had nearly incapacitated him.

“Ten more?” Chane asked in disbelief. “In these mountains, with nothing to feed upon but those few still alive?”

“No,” Welstiel answered. “Ten taken. Not ten undead . . . yet.”

Chane noticed the brown glass bottle in his companion’s hand.

“Not all rise from death,” Welstiel said. “If I am fortunate, perhaps a third of these will.” He held out the bottle. “Drink half. You have duties, and I need you whole again.”

Chane recoiled. That chained beast inside him struggled against its bonds at being offered more scraps of gristle.

He was trapped not only by the sun but by what little life remained here. Where else in these winter mountains could he hope to feed enough to reach civilization? He was trapped as well by his hope for a future. That was the true manacle around his neck—and Welstiel held its chain.

Chane took the bottle.

Lost in dormancy, the sleeper heard a cry. A second, then a third unintelligible voice joined the first, alternating and growing in volume. The sleeper shifted and began to rouse.

But in the dark, a brief glint vanished. Too quick in its retreat, the flicker seemed like a light upon something huge and black undulating in the dark.

Chane awoke upon the entry room’s stone floor and sat up quickly. He had never dreamed in dormancy before.

Muted moans and cries drifted down the stairwell, and Chane took brief relief in realization. The sounds had come from the dead rousing in the cells, not in his dream, and the glint in the dark, as if something moved . . .

Chane turned around.

A dim line of fading light stretched across the floor. The last of dusk’s light crept between the window’s shutters. The low fire still burned in the hearth, but the young priest’s withered corpse was gone, and Welstiel was nowhere in sight. Only then did Chane notice a dim light at the top of the stairs.

The moans and agonized calls pulled at him. He took slow steps up the stairwell and saw a lantern upon the floor. Welstiel sat upon a stool just beyond it in the passage’s near corner.

“Six,” Welstiel whispered, his voice laced with astonishment. “Can you hear them? Six of ten, all risen. My highest hope had been three.”

Chane barely heard him as longing surged at the smell of blood still on the floor. Panicked mewling escaped through the spaces below the cell doors and echoed along the stone walls. Or were they only in Chane’s mind?

The second door on the left rattled.

It shuddered twice as something rammed against its i

nner side, and then lurched as it was pulled hard from within. A sharp grating of metal on stone snapped Chane from his morbid fascination. In place of wood shards, each door handle on the left was jammed with a plain iron shaft.

“You will now watch over them,” Welstiel said. “I have other preparations to make.”

Chane caught the implication. “You have been here watching all day? How . . . how could you keep from falling dormant?”

Welstiel ignored him. More iron bars leaned against the wall beyond his stool.

“You plan to drain more of them . . . and brace them in?” Chane asked.

Welstiel shook his head, still watching the one shuddering door. “The spare bars are for when one is no longer enough.”

Chane stared at Welstiel, confused. Had the man abandoned all reason amid a night of gluttony, driven over the edge by his revulsion for feeding? Living priests were still trapped in the right-side cells—to satisfy the appetites of Welstiel’s newborns. If he knew his creations would break free, then why wait to reinforce the doors? And why keep his new servants locked up at all?

As if reading Chane’s thoughts, Welstiel answered. “To let them hope they might yet break free and feed . . . and as reason fades and desperation grows, to take that hope—and sanity—and leave only the hunger.”

Welstiel headed downstairs as Chane stared numbly after him.

“Do not let them out,” Welstiel warned softly, pausing at the bottom. “And if by chance you glimpse one through the crack of a straining door . . . do not look in its eyes. You may see too much of yourself reflected there.”

Chane backed into the corner, settled upon the stool, and closed a hand tightly upon a spare iron rod.

He couldn’t choose the greater madness surrounding him inside this fortress.

Was it the new undeads within those small cells, or was it Welstiel, who had made them?

Welstiel retrieved his pack and headed down the passage off from the front door. He had made it through the day without falling dormant—without a visitation from his patron of dreams. But he would not get through another such day without aid.

He opened the few doors along the way but found only storage rooms, not quite the private place to safely sift through his belongings. The passage’s end spilled into a wide room with long rough tables and benches—a communal meal hall—and he wasted no time looking about.

Welstiel threw open the pack’s flap to dig inside and withdraw a frosted glass globe. Three dancing sparks of light flickered within it. Their glow brightened at his touch, enough to illuminate the table. Fishing again, he retrieved the iron pedestal with the hoop on top and set the globe upon it. Then he opened the pack wider.

Years had passed since he had needed to drug himself. He pushed aside books, metal rods, a hoop of marked steel, and the box that held the cup with which he fed. At the pack’s bottom, his fingertips brushed soft fabric over something more solid. He pulled out this hidden object wrapped in a sheet of indigo felt.

Welstiel unwrapped the covering, exposing a thin box bound in black leather, and tilted the lid up. Inside were six glass vials cushioned in felt padding, each with a silver screw-top stopper. All but one were empty, and that one was filled with murky liquid like watery violet ink.

Two doses per vial, and one dose could stave off dormancy for a few days at best. He needed much more—as much as he could make. Tonight, he planned to search the monastery for the components to create more. Hopefully the hidden enclave of priest healers would have the supplies he required.

He was done being a puppet—done with his dream patron.

From here on, he served only himself, and had no wish to meet those black coils in his dreams ever again. He unscrewed the one full vial and a fishy sweet scent filled his nose as he downed half its bitter contents.

Welstiel grimaced, wishing for tea to wash away the taste. He closed the vial and returned it back to its padded slot. Once the box for his concoctions was sealed and rewrapped, he tucked it in the bottom of his pack.

The orb of his desire, the promised artifact from the world’s lost past, was locked away in an ice-bound castle guarded by ancient ones—vampires. When he gained it, he would never feed on mortals again. Or so his dream patron had told him.

Once, he had believed that controlling Magiere, his dhampir half-sister, was the way to acquire this treasure. But her actions grew more and more unpredictable. Still, one phrase whispered by his dream patron rang true.

The sister of the dead will lead you.

Though his patron was often evasive or deceitful, Welstiel believed these few words. In dream visitations to that six-towered castle, he had seen a figure upon its steps, waiting at the great iron doors. He knew he needed Magiere. She was necessary, either to find or to gain entrance to that place, or merely to face its guardians as a hunter of the dead. But if Welstiel could not control her directly nor trust his patron, he would need more than Magiere to assure his success.

He needed minions—mindless, savage, without mortal weaknesses—to serve him in the coming days.

He needed ferals.

Halfway through the third night’s vigil, Chane’s reason began to fracture. He could barely hold off the false hunger brought on by the wails and hammering within the cells. And though he tried to bury himself in memories of Wynn and fancies of an existence far from this place, it did not work.

At the sound of splitting wood, Chane lurched to awareness and rushed the first door on the left.

The top corner above the latch warped inward. Pale fingers with torn and split nails wedged through the space. They were smeared in fresh and dried black ichor. Chane slammed an iron bar against the wriggling knuckles.

An outraged snarl erupted behind the door, and the stained fingers jerked from sight. The door slapped back into its stone frame, and Chane jammed a second iron bar through the handle.

He covered his ears, trying to shield himself from the yelps and moans and scratching upon wood. Then he retreated down the corridor to the far end—as far as he could get without fleeing the upper floor altogether.

To hunt . . . feed . . . and the blessed release of blood filled up his thoughts.

His gaze drifted to the other side of the passage, and the doors barred only by wood.

How long would Welstiel starve his new children before feeding them? What if there was not enough for them—or nothing left for Chane but Welstiel’s little cup? He turned away from the doors, and his gaze fell upon the sixth right-side cell. Its door was still ajar from Welstiel’s night of gluttony.

Chane shuffled over to look inside, though his lantern left by the stool provided scant light, even for his keen night vision. A shadowy stain of congealed and dried blood marred an old canvas pillow on a plain bed. Little else in the room promised distraction from torment, from a small discolored chest of tin fixtures to the oval rug woven from faded fabric scraps. The little bedside table . . .

Chane’s eyes fixated on the book resting there. He stepped in and seized it.

Its page edges were rippled from long use, and he felt deep creases in the thick leather cover. Old but well crafted, what use would religious recluses have for such a soundly bound volume? Chane stepped out into the passage for better light.

The cover’s gilded lettering was half-gone, but he still made out the title written in old Stravinan.

“The Pastoral Path,” Chane whispered, and flipped pages at random.

It was a book of poetry and verse. He stared into the vacant room, wondering about its previous occupant. Why would anyone living such an austere existence want a poetic work?

A sudden twinge tightened Chane’s shoulder and the side of his neck.

He headed back to his stool, skirting the cells of the living but averting his eyes from those of the undead. But as he settled in the passage corner, the book still in hand, he could not stop gazing at those silent doors on the right, their handles barred with only wood. A nagging, unformed thought turned in the ba

ck of his mind.

With it came a fear he didn’t quite understand.

He flung the book down the passage. It skidded until it caught in the congealing pool of blood.

A loud screech from the first barred cell brought Chane to his feet, and he grabbed another iron rod. He heard wood breaking, followed by growls of fury, but the door did not buck in its frame this time. Something was happening inside the cell.

One voice—female—screamed louder than the first. Her sound was smothered by the hungry wail of a third. A pain-pitched shriek ripped out of her, along with the sounds of tearing cloth and bestial snarls. Her voice broke in panting sobs, then gags. A wet tearing followed.

Chane stood staring at the door, unable to move.

Struggles within the cells faded more each night, but by the fifth, Chane was almost deaf to them.

Welstiel stepped out of the stairwell.

He was dressed in black breeches and faded white shirt, and carried water skins and small sacks that smelled faintly of old bread. He approached the first door on the right, opened it, and tossed in a water skin and a sack. Before anyone within could speak or move, he slammed the door and reinserted its wood brace. He repeated the process twice more.

How often had he done this?

“We must keep them alive,” Welstiel said absently and then tilted his chin toward the stairs.

Chane’s night watch ended once more, and he slipped down the stairwell.

Each dawn, he’d discovered small oddities about the entry room. Nothing extraordinary, but something different each time. One night, Welstiel’s pack had rested by the fireplace. Strange rods of differing dark tones peeked out the side of its top flap, but Chane was too mentally worn to be curious. Later, he had noticed the old tin teapot near the hearth, but no cup in sight and no lingering aroma of brewed tea.

On the fourth night, the room was more orderly but smelled of crushed herbs—and something fishy and sweet that Chane could not identify.

Tonight, Welstiel’s pack sat upon the bench, and beside it rested a small bottle and a leather-bound box, longer and narrower than the walnut one which held his brass feeding cup.

Chane had never seen this box before.

Child of a Dead God

Child of a Dead God